When entering the Nagatasenkoujou workshop, it’s impossible not to notice the six vats carved on the floor, on the right. Usually we are greeted by Beck, the lovely shiba inu mascot, and the blue bandana around his neck can provide a clue about these vats. This is the last workshop in Izumo, in the Shimane province, dedicated to the dyeing art of Tsutsugaki Aizome. And it’s one of the two or three remaining in all Japan.

Aizome is the name by which indigo dye is known in Japan. Today most of it is done using a chemical process, but the Nagata family keeps doing it in the traditional way. “It’s not the same thing”, says Masao Nagata. “With chemical dyeing the color is released, but with traditional dyeing the color remains and does not transfer to the skin”. Anyone who’s ever had a blueish tint on their skin after wearing a brand new indigo gi or hakama, knows exactly what he is talking about.

The Nagata family came from Tokushima to Izumo in the end of the XIX century. At that time there were about 60 or 70 dyers in the region. Today only Shigenobu and Masao Nagata, father and son, remain. They are the fourth and fifth generation of dyers in the family.

The process itself begins with master Shigenobu drawing on a white cloth the motifs that will be printed, usually traditional japanese drawings. Then, using an adhesive paste made of glutinous rice, he delineates the contours. After that, he applies rice bran which helps the paste to set on the cloth. The dye will not reach the places where the paste is set, which makes the end result a traditional drawing in white over a deep blue background.

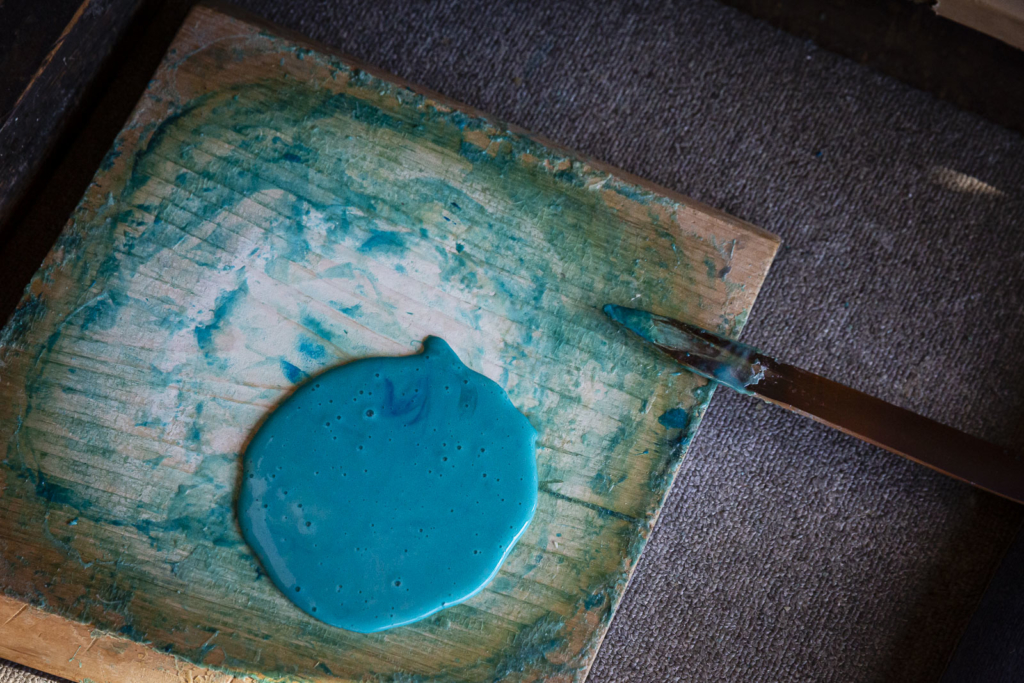

After that, his son Masao Nagata takes over the process. He will brush the cloth with lukewarm water to help create clear and crisp outlines for the motifs. Then he will dip the cloths on the vats where bacteria have been fermenting for two or three weeks. First the cloth will take on a greenish yellow color, which will then turn to green, and finally blue when it dries. He repeats the process as many times as necessary to obtain the indigo tonality that is required for the final results. Some cloths are just dipped two or three times for a light blue tonality, others are dipped ten to twelve times for a deeper indigo hue.

The bacteria living in the vats are responsible for this color. In reality they want to leave the water as quickly as possible, so they will cling to anything that is dipped on the vats. But outside the liquid they can’t survive for more than a few seconds, so they die shortly after. Their residue is what remains in the cloth, and gives it its color. The fermentation process uses dried plants, sake and other ingredients. Masao explains that he cannot let me know more about it, as it is a secret that is kept within the family.

When the dipping finishes, the cloths are washed on the small stream in front of the workshop, so that the paste is removed, and the white motifs are revealed on the indigo background. They will then be put to dry outside the workshop, if the weather is good, and after that, they are ready.

It’s hard to stay indifferent to these craft items once they are finished. The deep indigo is mesmerizing, and the traditional white drawings contribute to enhance the color even more. There really is something magical in following traditional processes rather than succumbing to the temptation of industrializing the process for mass production. I sincerely hope the Nagata family can continue with their process for many more generations to come.